Tony Rice Lessons

What I learned during nearly 50 years of listening to, watching, trying not to be influenced by, and studying the music of the great Tony Rice.

I first heard about Tony Rice in 1973 or ’74 in a review in the County Records newsletter, which raved about his debut album Guitar. I had been trying to play bluegrass and old-time music on the guitar for about a year, and I idolized Doc Watson, Clarence White, and Norman Blake, but the review talked about Rice’s ability to match the other bluegrass instruments’ power in a way that hadn’t been done before (or so I remember). So, I ordered the album from County’s mail-order division—the only way for a West Coast teenager to get bluegrass records back then—and when it arrived I was stunned, not just by Tony’s power and virtuosity on “Freeborn Man,” “Salt Creek,” and “John Hardy,” but by the fat, clear tone and resonance of his guitar on “Faded Love.” At the time, most of what Tony was doing was way beyond my technical ability, but from that day, I’ve been trying to get my guitar to sound like Tony’s did on that record.

The evolution of my guitar playing took many paths after that, and it would be fifteen years before I had a regular gig in a bluegrass band (Laurie Lewis and Grant Street, from 1989–91), but I always kept my ears open for what Tony was doing. Sometimes I ended up down a rabbit hole of interest, though I wasn’t really playing bluegrass at the time, obsessed over his album Manzanita, for example, or the first David Grisman Quintet album or the now legendary JD Crowe and the New South album.

In the first half of the 1970s, the dominant flatpickers—Tony, Clarence, Doc, Norman, Dan Crary, Russ Barenberg—all had different styles. But by the time I’d found my way back to the bluegrass world—after a decade playing various kinds of jazz as well as old-time and Irish music on the fiddle, Cajun and country music on the electric guitar, and backing a variety of singer-songwriters—Tony was king. Everyone, it seemed, played like Tony, or at least they played a somewhat simplified version of his style centered around his signature bluesy hot licks. But the problem with a musical style defined by copycats is that it’s easy to forget what the original sounded like. Yes, everyone played Tony’s hot licks, but nobody played the way he played on “Church Street Blues” or “Faded Love” or “Blue Railroad Train,” unless they were trying to play his solos verbatim. One thing I liked about the flatpicking scene when I first discovered it in the early ’70s was that everyone sounded different, but entering a world where everyone (with a few notable exceptions) was just trying to sound like Tony made me underappreciate his playing, and I was determined to avoid his influence.

When I joined Laurie Lewis’s band the main thing I had to work on was playing solid, effective rhythm, so I listened to a lot of rhythm guitar players, including, of course, Tony. But one close listen to Tony’s playing told me that he should not be a model for my rhythm playing. It was too complex, too individual, and well, almost too powerful. Tony’s rhythm playing drove the bands he played with; his guitar said “this is how it goes, follow me.” I, however, being a somewhat inexperienced bluegrass rhythm guitarist, needed to find a way to fit into a band that already had a rhythmic director; my role was to help make all the instruments in the band gel. But that close listen to Tony’s playing made me realize how much I’d missed, and how much he differed from his copycats. And that made me go back and listen to some of the records I’d neglected, especially Church Street Blues and the first duet record he made with Norman Blake, but also some of his “singer-songwriter” records like Native American and Me and My Guitar.

As I was on the road a lot at the time, I was lucky enough to hear Tony live at festivals a few times a year, with the Tony Rice Unit (at that time the version with his brother Wyatt on rhythm guitar, Jimmy Gaudreau on mandolin, and Mark Schatz on bass) but also in various all-star festival bands, usually including Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Béla Fleck, Mark Schatz, and either Mark O’Connor, Stuart Duncan, or Vassar Clements on fiddle. Being festival performances, they featured Tony’s driving, flashy side.

Vocal problems required Tony to stop singing in the mid-’90s, and while this was a tragedy for his fans, it must have been incredibly difficult and demoralizing for him. I don’t think I realized how much until he told me one night, after sitting in with Tim O’Brien’s band (which I played guitar with from 1992 to 1997), “I envy you. You have a great gig. I’d love to play Tim O’Brien songs every night.” I later realized that losing his ability to sing had effectively made him a sideman. And as he was unable to play the songs he liked to sing—especially the folk and pop songs on those “singer-songwriter” albums by Gordon Lightfoot, Bob Dylan, James Taylor, and other contemporary folk songwriters—he was confined to playing instrumentals or backing up guest lead vocalists, who, of course, could choose the songs, the tempos, the grooves. But Tony Rice was never a sideman. Even when he was playing guitar with JD Crowe and the New South, the David Grisman Quintet, or the Bluegrass Album Band, he functioned as more of a co-leader, and his guitar and voice defined the sound of those bands as much as their official leaders did.

Tony’s life, however, had never been an easy one. In an interview I did with him in the late ’90s, he talked about the time after he left David Grisman’s band: “I was with Grisman from the fall of ’75 to the fall of ’79. The Tony Rice Unit didn’t really play until the fall of 1980. It was Todd Phillips, John Reischman, and Fred Carpenter. That band really didn’t really gig that much. We did one tour of the East and occasional gigs in California. In ’79 and ’80 there was a real bad slump in the music biz and it was hard to find gigs that paid decent money. It’s hard to ask guys to come over to your house to rehearse to do an opening act where you’re not going to get paid anything. I went musically dormant for a while from ’84 to ’85. I got through some personal difficulties.”

And David Grisman told me in an interview about the founding of the original David Grisman Quintet, “I wasn’t out to form a band. These guys were just coming over to play. I spent three days at Tony’s house in Lexington, and then he came out [to California] after a New South tour of Japan. He kept saying ‘When’s our first gig?’ and I’d say ‘We gotta rehearse.’ It just didn’t seem that viable.”

When I interviewed Tony after the release of the Rowan and Rice album Quartet in 2007, he told me, “My playing was more straight-ahead up until about ten or 15 years ago. Then I started to get arthritis in my right hand, and now I have tendinitis real bad in my left hand—over ten years or so. That’s really changed it even further. I’ve slowed down; I don’t play that many fiddle tunes or real fast breaks anymore.”

Making a living as a creative musician isn’t easy for anyone. Even if you’re universally recognized as the greatest bluegrass guitarist in history and the bands you were in (DGQ, New South, Bluegrass Album Band, Tony Rice Unit) are still major influences on the way bluegrass and progressive string band music is played today, forty or fifty years later.

An interview with Tony Rice

For the interview I did with Tony in 2007, I got him to bring his guitar along, and we treated the interview more like a lesson, with him demonstrating things on the guitar that we talked about. Here are some excerpts from that interview (download the PDF to see the musical examples referenced in the interview): Tony Rice Lessons (pdf)

There’s a way you have of playing melody that’s a sort of modern Carter Family style.

TR Well, you know, the first thing I learned was “Wildwood Flower,” early Carter Family things—“The Storms Are on the Ocean,” stuff like that. Here, I’ll play a little bit [Example 1]. Of course, when I learned it, it wasn’t like that [laughs].

You’re crosspicking, but it’s not the traditional banjo-style crosspicking Clarence White and George Shuffler did.

TR No, I never have done that.

Your crosspicking reminds me of the way a piano player might play a melody and then fill in the spaces with arpeggios.

TR Yeah, you know, at heart, I am an acoustic piano player.

Did you have any role models when you started?

TR Well, back then there was no bluegrass [lead] guitar; it didn’t exist. The first stuff I ever heard was Flatt and Scruggs, the Monroe Brothers, Delmore Brothers. Probably the first guitarist I heard play what you would consider a solo in an arpeggio form was Earl Scruggs fingerpicking “Jimmie Brown the Newsboy.” I mean, Clarence White wasn’t even playing lead back when I was doing that stuff.

So, when you knew Clarence, he was just playing rhythm?

TR Yeah, that’s the only thing he knew. I remember when Roland got drafted into the Army, the only lead guy they [the Kentucky Colonels] had was [banjoist] Billy Ray and occasionally Leroy Mack on dobro. So, Clarence started taking an interest in playing some lead stuff on the guitar—some ideas that he got from his brother [Roland]. And he just evolved into his own musician.

You played together, right?

TR Yeah, sure, but I couldn’t play like him—I still can’t play like him. Nobody else can either [laughs]. It’s been an interesting ride, I tell ya, to watch this whole scheme of things, from a time when there was no bluegrass guitar to what it has evolved to now.

I’m curious about your right-hand picking technique. Unlike someone like Doc and most flatpickers these days, you don’t use a strictly alternating style of down-up picking.

TR Right.

It seems to me that what you’ve done is found the most efficient way of picking any given group of notes.

TR Yeah, combined with pull-offs. I use a lot of pull-offs, and try to make them sound like they’re actually plucked notes. My playing was more straight-ahead up until about ten or 15 years ago. Then I started to get arthritis in my right hand, and now I have tendinitis real bad in my left hand—over ten years or so, that’s really changed it even further. I’ve slowed down; I don’t play that many fiddle tunes or real fast breaks anymore.

But you’ve expanded your playing in other ways.

TR Yeah. Sometimes in the middle of a solo, I’ll weave in a couple of chord patterns—use a sequence of chords as an integrated part of a solo [Examples 2 and 3]. I find myself doing more and more of that.

Your playing seems very free these days—like you’re allowing all your ideas to come out and you’re not afraid to take chances.

TR No, I’m not. It’s just one big circus of looking for something to keep from boring myself [laughs].

The solo on “Walls of Time” [from Quartet], where you go into double time, reminds me of Coltrane. Did that just happen in the studio? Or did you plan to do that?

TR I don’t know when I started doing that. It probably happened on one of those nights in some juke joint somewhere, where you don’t really give a shit. And you just go, “Well, Peter kicked the tune off slow enough, but I can’t hardly play it that slow. I’m just going to play it double time, just to get through it.” So, it evolved from there.

You also occasionally use your middle and ring fingers along with the flatpick—not just in solo pieces, but also in your lead lines.

TR A few things, yeah. You can’t do it so much on a steel-string guitar; you’re not going to have any fingernails left—you’ll rip ‘em all to shreds [Example 4]. Stuff like that, you can’t do with just a roll of the flatpick.

Have you been doing that for a while?

TR Oh, 20 or 25 years, I guess. I don’t even know when I started doing it.

Obviously, it works when you’re playing solo pieces, but how often do you use your fingers with a band?

TR It depends on how well you can hear onstage. If it’s a situation where you’re having to play really hard, then I couldn’t dare get away with anything like that. But there are other times when you’ve got a good monitor system and you can hear every little nuance of what you’re doing. If that be the case, I’ll use the other two fingers. But other than that, if it’s not a good sound system, I won’t. Because you don’t have any power when you do that. You don’t have power like you do when you’re playing rhythm or lead with a pick.

You recorded a couple of beautiful solo arrangements of “Danny Boy” and “Shenandoah” on Unit of Measure. Are there any other solo arrangements you’ve been playing lately?

TR I’ve been working on this thing for years: “Barbara Allen” [Example 5].

You’ve also been revisiting old material lately: the Manzanita set at RockyGrass, some songs on the Quartet CD, the tour with Alison Krauss. Do you like going back and looking at those old tunes like “Blue Railroad Train”?

TR Well, I’m going to have to. [Example 6] Stuff like that, I’m going to have to brush up on.

You also recorded a new version of Peter’s “Midnight Moonlight” on Quartet. The way you play backup on some of that reminds me of the rolling feel Clarence White would get on electric guitar with the Byrds—for instance, in the solo section, when you go to a Bb chord up the neck.

TR Yeah, the vamp section goes from G to Bb [Example 7]. Sometimes I’ll throw an F in there with a Bb in the bass.

When you’re soloing on that G–Bb vamp, are you consciously thinking of moving between a G scale and a Bb scale?

TR Well, the Bb is relative to the G. So out of a G, you can use Bb, or you can stay in the same mode and play out of a regular G with no third, and then play out of Bb, or C, or F. It’ll work with all those chords. Once the rhythm section goes to Bb, I just say “Well, I can play everything I want to play in G.” F will work [Example 8]. There are a lot of things that will work with that vamp.

With Peter, your backup and rhythm style has really evolved. It’s very different from how you played in the Tony Rice Unit or the Bluegrass Album Band.

TR Yeah, and it’s been cool to do that. Peter and I started playing together in about 1998, and when I first started gigging with Peter it was just him and me; there was no rhythm section. It was pretty straight-ahead what I had to do: just solo and play alternate chord inversions to what Peter was doing. But when we started playing as a quartet, all of a sudden I found myself with a rhythm section. So, all I had to do was play a solo and the rest—it didn’t matter what I did. I could substitute any chord I wanted to. Just through the process of trial and error, I would come up with substitutions that I had learned from my jazz heroes. It’s really been fun to do that.

It’s a beautiful sound. And once again, it reminds me of a piano player’s role.

TR Yeah, I think, “OK, if somebody set McCoy Tyner onstage to play acoustic piano with the Peter Rowan band, what would he play?” Or Bill Evans, or Oscar Peterson. I think like that: “What would these guys do?” It’s not anything I go home and work on. I work it out on the fly, onstage. It’s one of those circumstances or musical formats you’re in where you’re free to experiment all you want, because you know within a certain framework how far you can go and stay within those boundaries.

*

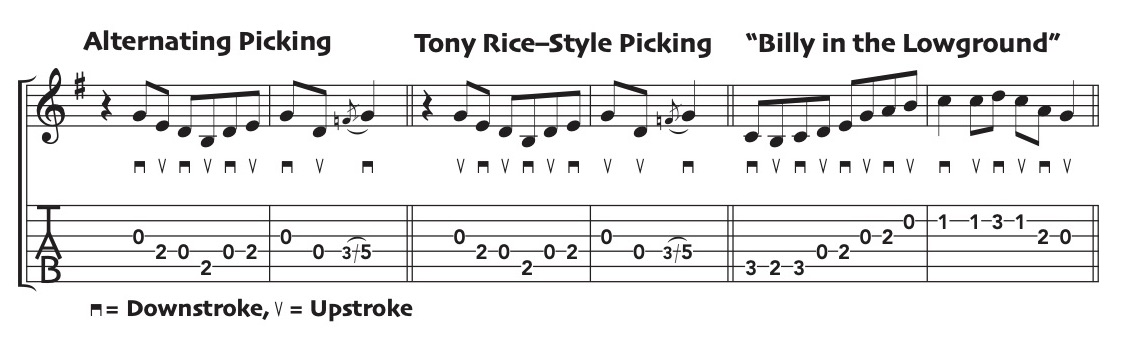

That interview, and the transcriptions of Tony’s playing I did, made me really delve into his picking technique. Tony began playing lead guitar at a time when there were few role models and certainly no instruction books or videos. Even in jazz, guitarists were using a variety of techniques to play solo lines (Charlie Christian supposedly used all downstrokes, Wes Montgomery used his thumb). Today, most bluegrass guitarists use an alternating style of picking in which the pick moves down on all the quarter notes in a measure and up on the ands or eighth-note offbeats.

Observers of Tony’s picking have long known that he doesn’t follow a strict picking pattern, and some think that his choice of pick strokes is almost random—or that he just picks in whatever direction he wants to at a given time. But my transcriptions revealed that he had developed a very efficient and systematic way of picking that combines elements of a number of techniques, including alternating picking, the “down-down-up” style of traditional crosspicking (though not in a repetitious manner), and “sweep picking” (in which the pick sweeps from string to string with either a downstroke as it moves down across the strings or an upstroke as it moves up across the strings). To put it simply, given any particular group of notes, Tony always uses the most efficient method of picking them, regardless of where they fall in the beat.

To break this down, consider that there are two ways of striking a string with a pick: a downstroke or an upstroke. If you play a downstroke on the third string, your pick will then be in a position slightly below the third string; at that point, the most efficient options are to play the third string again with an upstroke or to play the second string, either with an upstroke or downstroke. As for the upstroke, if you play the third string with an upstroke, your pick will be in a position slightly above the third string. Then the most efficient options are to play the third string again with a downstroke, or to play the fourth string with either an upstroke or a downstroke.

So, if your pick is remaining on one string, the alternating method is the most efficient—but isn’t necessarily the most efficient once you start changing strings. And the most efficient pick stroke depends on which string you’re going to play next. For example, if you want to play a note on the third string and follow it with a note on the fourth string, it’s more efficient to play the third string with an upstroke. If you want to follow a note on the third string with a note on the second string, it’s more efficient to play the third string with a downstroke.

For example, look at the kickoff Tony often used on “Nine Pound Hammer.”

The first example shows a strict alternating pattern and the second shows how Tony played it. The first bar of Tony’s method is the complete opposite of alternating picking—with upstrokes on the downbeats and downstrokes on the ands—but notice how much more efficient the picking is. Now look at the second bar. After playing the G note with an upstroke, Tony’s pick is in position to play the D string that follows, but here he has a decision to make—whether to play it with an upstroke or a downstroke. Since it’s going to be followed by a slide up to the fifth fret on the same string, he uses an upstroke. (If he was going to play a note on the G string, he would have played the D with a downstroke.)

The first couple of measures of Tony’s version of “Billy in the Lowground” show that he’s not just “playing backward,” as the “Nine Pound Hammer” intro might suggest. He starts with alternating picking, because that’s the most efficient way to play this group of notes. But in the second bar, he flips it around, starting the next series of eighth notes with an upstroke to avoid his pick having to jump backward to play the A note on the second fret of the G string.

Of course, Tony makes all these decisions intuitively, the result of a lifetime of playing. Although his style could be termed “efficient picking,” playing this way is incredibly difficult and requires an amazing degree of pick control and an unerring sense of time. (Note to flatpickers: I’ve seen excellent players try to copy his picking method, and other than Tony’s brother Wyatt, nobody has managed to pick like Tony and play in time.) One reason that alternating picking has become popular is that the metronome-like back and forth of the picking hand provides an easy way for the player to keep time. But Tony’s time originates in his left hand—in the notes he wants to play. Which means that his melodic and harmonic ideas come first, and the technique he uses to play them follow after. It’s hard to imagine a more musical approach to technique.

*

When I heard that Tony had passed away on Christmas Day, 2020, I was watching a video of the Tony Rice Unit playing at the Strawberry Music Festival in 1986. The idea that he was gone struck me like it must have struck millions of people who have listened to and loved his music. The way I dealt with his loss was to dig into his music again and remember my few encounters with him. He was always kind to me and encouraging, and he didn’t have to be. He treated me like an equal; in interviews he often followed a revealing statement about guitar playing with, “Ah, but you know all that.”

I’ve learned so much about music from Tony over the years, directly and indirectly, but the thing that will always stay with me is that Tony could only ever be who he was, and who he was was unique, even though he had many imitators. This wasn’t always easy for him, and may have made his life harder. I can only hope that at the end Tony had some idea of the effect he had on so many lives and such a wide range of musicians and styles of music, that he understood how much joy he had brought to people all around the world, and that he found some peace amidst the pain.

Related Breaking News Posts

|

Now Available for Subscription | Creating Bluegrass and Roots Music Solos with Scott NygaardLearn how to turn scales and arpeggios into solos that sound great, whether you’re improvising or playing a composed solo. Read More |

|

Bluegrass Guitar Fingerboard Mastery with Stash Wyslouch Now Available | New Course!Decode the mysteries of the guitar neck through the lens of bluegrass, old-time, and country music with this new course from guitar master Stash Wyslouch. Read More |